The Forgotten Pioneer: Joan Shogren and the Dawn of Computer Art

In the sleek galleries of digital art museums today, where AI-generated portraits fetch millions and NFT collections dominate conversations, there exists a curious historical void. A foundational figure remains conspicuously absent from our collective understanding of how algorithmic creativity began. Her name is Joan Shogren a chemistry-educated departmental secretary who, in 1963, orchestrated what evidence suggests was the world's first public exhibition of computer-generated art, predating better-known European and American showcases by nearly two years.

The Secretary Who Taught Computers to Make Art

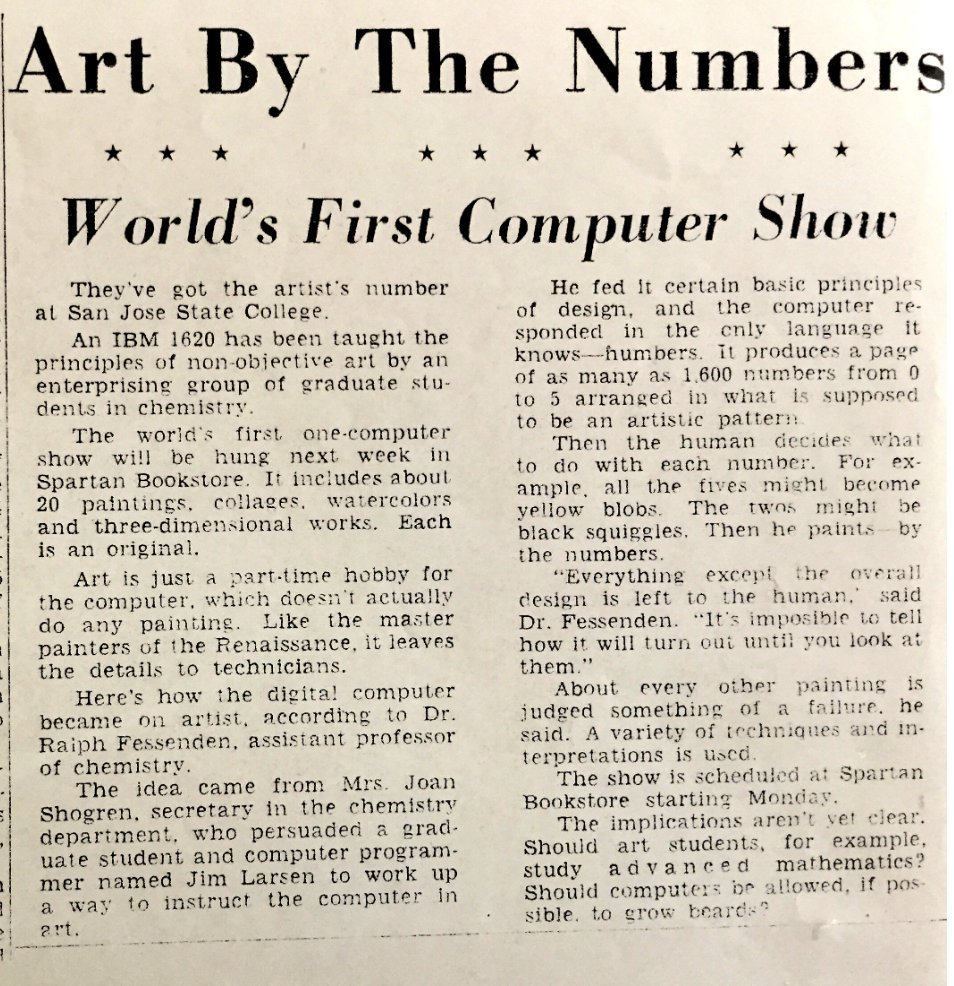

Before the advent of smartphones, tablets, or even rudimentary graphic interfaces, Shogren intuited something remarkable: that a computer might be taught the "rules" that artists follow. As a chemist by training and a departmental secretary at San José State University, she inhabited an unusual intersection between scientific methodology and administrative access to early computing resources. In May 1963, she articulated her vision to colleagues in the chemistry department graduate student Jim Larson and assistant professor Dr. Ralph Fessenden who shared her curiosity.

"Such items as proportion, balance, and a center of interest are what we ask the computer to work with," Shogren explained in a contemporary interview with the university newspaper. This deceptively simple statement represents a profound conceptual breakthrough. She had essentially articulated the fundamental premise underlying algorithmic aesthetics: that artistic principles could be translated into mathematical instructions a machine could process.

The execution was ingeniously pragmatic. Using an IBM 1620 a room-sized early digital computer the team fed punch cards containing Shogren's encoded "laws of art" into the machine. The output? Nothing so visually sophisticated as today's digital creations, but rather a grid of numbers resembling "an income tax table," as one observer noted. Each number corresponded to a particular color or shade, essentially creating a primitive form of pixel art through numeric code.

The team then plotted this numerical grid onto canvases where human hands (often those of senior chemistry student Marvin Coon) would hand-paint shapes squares, rectangles, triangles according to the color values assigned by the algorithm. The result was a hybrid creation: compositions dictated by digital algorithms but realized through analog means, producing abstract, mosaic-like paintings that represented the first tremors of the digital art revolution.

The Exhibition That History Forgot

On May 6, 1963, in the unassuming venue of the SJSU campus bookstore, Shogren exhibited these computer-generated works, creating what historical evidence indicates was the first public display of computer-generated art anywhere in the world. This modest campus showing predated the widely recognized "first" computer art exhibitions Generative Computergrafik in Stuttgart (February 1965) and Computer-Generated Pictures at New York's Howard Wise Gallery (April 1965) by nearly two years.

The revelation of Shogren's precedence came through recent archival research by art historians including Paul Brown and personal records maintained by Shogren's family. For decades, the 1965 exhibitions were erroneously cited as the genesis of publicly exhibited computer art. This historical oversight reflects a broader pattern of marginalization that has frequently occurred in technological history, particularly regarding women's contributions.

Contemporary reactions to her work veered between tentative fascination and existential alarm. When the San Jose Mercury News revisited Shogren's work in 1966, journalist Vicki Reed described the project's implications with a mix of wonder and dread, imagining great masters "turning over in their graves" at the prospect of computer-generated art. Reed declared that "art simply never again will be a personally-human expression" thanks to Shogren's invention a proclamation that foreshadowed contemporary anxieties about AI's creative capabilities.

Shogren herself remained optimistic and nuanced about the relationship between human creativity and computational assistance. With "a pixie smile," she insisted "indeed computer art is art," explaining that "what the computer produces comes out on a sheet of paper to be artistically and individually interpreted by the technician." In this remarkably sophisticated view, she positioned the computer not as a replacement for human creativity but as a collaborative tool a perspective that anticipated current discourse about human-AI creative partnerships by nearly six decades.

The ClickArt Revolution

After her pioneering work in algorithmic art, Shogren's career took another innovative turn. In 1984, as personal computing emerged, she joined a Silicon Valley startup called T/Maker to create something now ubiquitous but then revolutionary: the world's first commercial digital clip art library.

Using early Apple Macintosh computers (sometimes prototype units obtained under non-disclosure agreements before public release), Shogren designed hundreds of small black-and-white graphics meticulously drawn pixel by pixel a process that co-founder Heidi Roizen described as "almost like needlepoint" due to the painstaking attention to detail required. Without modern design software, scanners, or drawing tools, Shogren placed individual pixels one by one to create images ranging from office equipment to holiday decorations.

Her ClickArt collections Publications, Personal Graphics, Holidays, Letters, and more democratized visual communication. For the first time, non-artists could incorporate professional-looking graphics into their documents, newsletters, and presentations. The concept proved transformative, with the ClickArt brand continuing for decades and ultimately being acquired by Broderbund. In a very real sense, the ubiquitous visual language of digital communication from emojis to stock photography traces part of its lineage to Shogren's pioneering pixel work.

A Legacy Reclaimed

The story of Shogren's contributions illustrates how technological history can become selective in its remembrance. Despite orchestrating what appears to be the first public computer art exhibition and helping create the first commercial digital graphics library, her name remains largely unknown even to digital art aficionados.

This historical amnesia stems partly from institutional factors Shogren worked from a chemistry department rather than an established art context, and as a departmental secretary rather than a professor or formal researcher. Her gender likely also contributed to her historical marginalization. Moreover, after her groundbreaking work, she focused on local projects and commercial applications rather than pursuing a high-profile art career or academic recognition.

Recent scholarly reassessments have begun to correct this historical oversight. Digital art historians have broadened their scope beyond the well-known male European and American pioneers to uncover overlooked figures, especially women. Institutions like the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Germany now include Shogren in their database of media art pioneers, acknowledging her as "a pioneer in the field of computer art" who realized the first exhibition of computer-generated images.

Art historian Judith K. Brodsky's 2021 book "Dismantling the Patriarchy, Bit by Bit: Art, Feminism, and Digital Media" highlights Shogren among women who made significant early contributions to computer art. Similarly, the Computer History Museum references her in online exhibits about the evolution of computer graphics and art.

The Visionary as Administrator

What makes Shogren's story particularly compelling is how she operated at the intersection of seemingly disparate realms: science and art, administration and innovation. Her background in chemistry informed her systematic approach to aesthetic principles, while her administrative position provided access to cutting-edge technology normally reserved for scientific research.

Her multidisciplinary curiosity spanning photography, graphic design, origami, chemistry, and computing enabled her to envision connections others might miss. When she suggested a computer could "design a picture" in 1963, she was articulating something genuinely revolutionary: that creativity could have a computational dimension. That this insight came from a departmental secretary rather than a celebrated artist or computer scientist makes it all the more remarkable.

Looking at today's landscape of AI art generators, algorithm-driven design tools, and computational creativity, we can see Shogren's early experiments as prescient precursors to contemporary developments. Her dual innovations algorithmic composition in 1963 and democratized digital visuals in 1984 anticipated two fundamental aspects of our current digital creative ecosystem.

As we continue exploring the ever-evolving relationship between human creativity and computational assistance, Joan Shogren's legacy offers both historical perspective and conceptual inspiration. Her work reminds us that technological innovation often emerges from unexpected sources and that the most profound insights frequently arise at the boundaries between disciplines. In her visionary blend of artistic intuition and computational logic, Shogren wasn't just ahead of her time she was helping to create the future we now inhabit.