The Rigorous Joker: François Morellet's Systematic Revolution in Geometric Abstraction

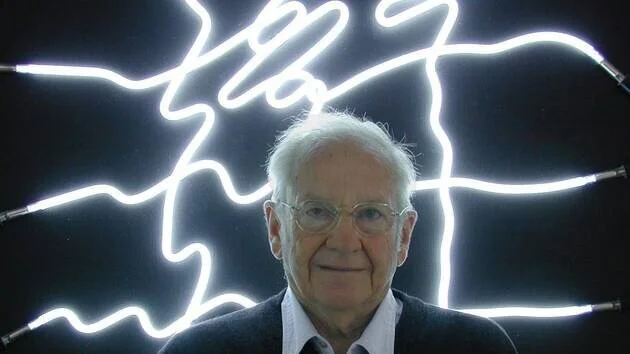

In the vast landscape of 20th-century abstraction, few artists have balanced mathematical precision with playful subversion as masterfully as François Morellet (1926–2016). Through his revolutionary approach to geometric art, this self-taught French visionary carved out a unique position at the intersection of multiple avant-garde movements while consistently maintaining his distinctive voice one characterized by an almost paradoxical combination of rigorous systems and mischievous humor.

Light as Material: The Neon Revolution

By the early 1960s, Morellet had begun pioneering what would become one of his most significant contributions: the incorporation of artificial light as primary artistic material. His inaugural neon work, "Néon 0°–45°–90°–135°..." (1963), featured white neon tubes on four panels blinking in interfering rhythms within a darkened room.

"The light source itself, not its reflection, [can be] regarded as a plastic material," Morellet noted in 1966, articulating the revolutionary potential of neon. This approach represented a radical departure from traditional painting, embracing the industrial "perfectly linear" quality of neon tubes as both medium and message. The piece was so intensely bright and rhythmically disorienting that it proved "quite unbearable" to viewers precisely the type of sensorial disruption Morellet sought.

Over subsequent decades, his neon installations evolved from the temporal complexity of flashing electrical circuits to spatial explorations that engaged directly with architectural environments. Rather than sequencing lights in time, he attached neon tubes in angular or curving arrangements that interacted with gallery walls, corners, and ceilings transforming entire spaces into immersive geometric experiences.

"L'Avalanche" (1996) exemplifies his mature approach to neon installation: thirty-six blue neon tubes suspended by fine wires, seemingly scattered at random through space. Despite its apparent chaos, the piece maintains Morellet's characteristic tension between disorder and system the scattered tubes follow a "rigorous yet visually disorderly plan," creating an immersive environment that dissolves the boundary between artwork and architecture.

Collective Experimentation: GRAV and the Active Spectator

Morellet's interest in viewer perception crystallized in 1960 when he co-founded the influential Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel (GRAV) alongside artists including Julio Le Parc and Francisco Sobrino. GRAV's 1963 manifesto "Assez de mystifications" ("Enough Mystification") proclaimed that passive art viewing should be replaced by active spectator participation.

This radical reconfiguration of the artist-audience relationship found expression in participatory environments like the labyrinthine installations GRAV presented at the 1963 Paris Biennale. These spaces, featuring Morellet's first neon pieces, were designed to engage viewers physically and perceptually through disorienting optical illusions, moving lights, and unstable visual fields.

"The group's activities including hands-on audience participation events like the 1966 'Day in the Street' in Paris reinforced Morellet's belief that art could be a playful scientific investigation rather than a solitary act of expression," notes art historian Serge Lemoine. This collaborative ethos challenged the romantic notion of the isolated artistic genius and anticipated later developments in installation and relational art.

Chance Operations and Predetermined Systems

Among Morellet's most innovative strategies was his early adoption of chance procedures to remove subjective choice from his compositions. Inspired by Jean Arp's Dadaist collages and John Cage's aleatoric music, Morellet began creating works determined by random number sequences drawn from telephone directories or the digits of π.

"Random Distribution of 40,000 Squares" (1960) exemplifies this approach. Morellet divided a canvas into a grid of tiny squares, coloring each red or blue according to a sequence derived from a phone book odd numbers dictating one color, even numbers the other. The resulting pattern appears random yet statistically balanced, creating a vibrating field that seems to pulsate with ordered chaos.

This mathematical method yielded what Morellet called "visually precise yet unpredictably generated abstractions." By establishing systems that produced visual outcomes beyond his control, he achieved a paradoxical freedom through strict constraint a central tenet of his artistic philosophy that aligned with contemporaneous experiments by the Oulipo writers group.

Architectural Interventions and Public Art

From the 1970s onward, Morellet expanded his practice into architectural space, creating what he ironically termed "disintegrations" site-specific interventions that dissolved the boundaries between art object and built environment. His first monumental architectural work appeared in 1971 on the Plateau de la Reynie in Paris (later the site of the Centre Pompidou), extending his linear grid systems into three-dimensional space.

These architectural projects culminated in rare institutional recognition when Morellet became one of only three contemporary artists honored with a permanent installation in the Musée du Louvre during their lifetime. "L'Esprit d'Escalier" (2010), created when Morellet was 84, incorporated his signature grid motifs into monumental stained-glass windows for the Louvre's Lefuel Staircase a striking juxtaposition of contemporary geometric abstraction within the museum's classical architecture.

"This permanent installation at the world's most renowned museum represented both institutional acceptance and Morellet's ability to engage meaningfully with architectural history," observes curator Alfred Pacquement. "The work's title a French idiom referring to clever thoughts that come too late reflects his characteristic humor even in this prestigious commission."

Legacy: Between Order and Chaos

François Morellet's enduring significance lies in his unique synthesis of seemingly contradictory impulses: Constructivist logic with Dadaist irony, mathematical precision with perceptual instability, systematic process with unpredictable outcomes. Over a six-decade career spanning painting, sculpture, installation, and architectural intervention, he consistently challenged conventions while developing a visual language of remarkable coherence.

Art historian Lynn Zelevansky characterizes Morellet's practice as operating "at the intersection of Minimalist aesthetics and Conceptual strategies, delivering the visual punch of Op and kinetic art while maintaining intellectual rigor." This intersection of formal innovation with conceptual depth explains his growing influence on contemporary artists working with systems, algorithms, and viewer participation.

Today, as digital artists employ algorithmic processes to generate visual outcomes, Morellet's pre-digital experiments with mathematical systems appear increasingly prescient. His early works using telephone numbers and π as random generators prefigured computational art while maintaining a distinctly human touch the tension between system and serendipity that animates all his work.

Perhaps Morellet's most profound legacy is his demonstration that rigorous abstraction need not be solemn or hermetic. Through his systematic yet playful approach, he expanded the definition of abstract art to include not just formal geometry but also interactive, intellectual, and humorous dimensions. As he once remarked with characteristic modesty: "My systems fix the rules and mathematics execute the composition... I always try to do the least amount possible!"

In this seemingly self-effacing statement lies the paradoxical brilliance of Morellet's contribution by doing "the least possible," he achieved among the most expansive and influential bodies of work in postwar European abstraction, one whose intellectual vitality and visual power continue to resonate with contemporary viewers.